Art takes many forms. Stone can be wrought, paper can be colored, an image can be captured on film. But art can also be found in unconventional places. We often forget to look for it in commonplace objects; ubiquity belies value. When an object is recognized for its utility, its perceived significance as artwork is even more greatly diminished.

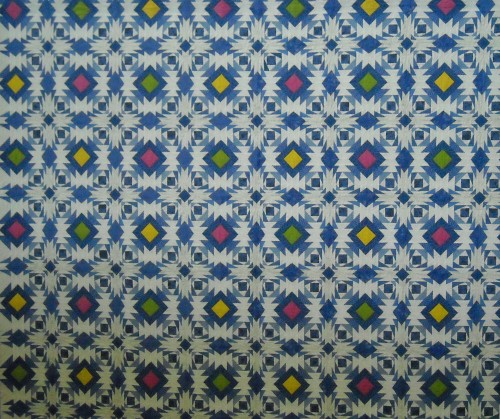

That is why many of us don’t consider a quilt a piece of art. It may look nice, but let’s be honest: it’s meant to keep us warm. It’s not art. Right?

As a museum and textiles consultant near Dallas, Texas, Marian Ann Matwiejczyk Montgomery ’77 has spent much of her career researching the role of quilts in the art world and their value as important cultural emblems. She has researched their role in various American subcultures and seen them become common displays in museums around the country.

“Quilts are major contemporary pieces of art,” says Montgomery. “They are misconceived as something done by little old ladies.”

As a consultant, Montgomery works with various museums and historical groups who look to put pieces of material history on display. Quilts have become a big part of this, but she also works with other historical textiles. To Montgomery, the fact that these items are made to be used is not a hindrance to their artistic value. Just the opposite, she says. An object that a person has used is easier to appreciate. An audience can relate to historic clothing and quilts because they can understand the value they held for the people who used them.

In that regard, her time at Central has paid dividends. “The education I got at Central was not only the book and classroom stuff,” she says. “It was relationships.”

At Central, it didn’t seem like Montgomery was on a path to a career in the art world. After graduating with a degree in home economics education, she taught for four years. But then she decided she was meant for something else. She left teaching to earn an M.A. in decorative arts and eventually completed a Ph.D. study through New York University.

After working for various institutions around the country, including The Sixth Floor Museum at Dealey Plaza (the Kennedy Assassination site), a museum in Tennessee where she curated her first collection of quilts and the Dallas Museum of Art, where she worked more closely with the art form, she made the decision to become an independent consultant in 1999. The first night she set out on her own, she got calls from three clients.

“I like the variety of projects,” she explains. “I would not have been able to do all the projects I’ve been involved with if I were at a single organization.”

She has worked with countless institutions across the country. The Texas State Fair archives, for example, as well as the American Association of Museums and the Park City Historical and Preservation Society. She even served on the team that opened the first women’s history museum.

All the while, she has seen society’s perception of quilts begin to change. She says museums today use them as a way to get people in the door. They’re popular displays. Like her, museum patrons appreciate the intimacy of quilts. “Quilting is very tactile; it’s very personal because of the interaction between the artist and the quilt,” she says. “When you see one, you want to touch it.”

Montgomery advises anyone interested in an arts career to follow a piece of advice given by one of her Central professors. “Bette Brunsting used to end each class by saying ‘go forth and do great things.’” Montgomery uses the words as the epigraph dedicating each of her books, and as a sentiment she applies to her own life.